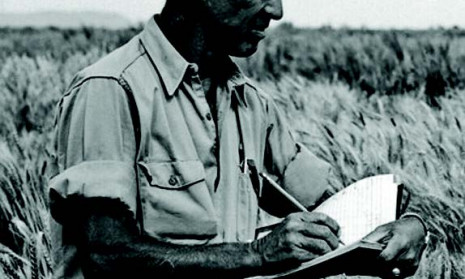

Norman Borlaug 1914-2009

This Issue of World Agriculture is dedicated to the memory of Norman Borlaug, who was born on a farm near Cresco, Iowa in 1914 and who won a Nobel Peace Prize in 1970. He died in September 2009 during the preparation for this journal of a paper of which he is a co-author. Borlaug always displayed remarkable personal stamina in his plant breeding research, working 12-hour days in harsh field conditions, where he challenged younger researchers with the physical prowess he had developed on the farm and through championship wrestling in his high school and university years.

By 1954 Borlaug and his colleagues had successfully bred what became known as "miracle seeds" of high- yielding dwarf varieties of wheat.

The new seeds produced greater yields in response to chemical fertilisers and other inputs. By 1956 his disease-resistant varieties had helped Mexico double its wheat production and, for the first time, become self- sufficient in grain.

By 1963, 95% of Mexico's wheat crops used the semi-dwarf varieties developed by Borlaug’ s team, and the harvest was six times as large as that in 1944.

In the mid-1960s, Borlaug's new varieties were being exported and adapted to local environmental conditions in the wheat growing regions of the world.

Notable beneficiaries were Pakistan and India , where, between 1965 and 1970, wheat yields nearly doubled, respectively from 4.6m tonnes to 7.3m tonnes , and from 12.3m tonnes to 20.1m tonnes . By 1974 India had become self-sufficient in producing cereals, and the germplasm and the technological improvements rapidly spread to all wheat production regions of the world. His introduction of high yielding semi-dwarf wheat to the developing countries of the world averted predicted international crises and famines, and he has been credited with saving the lives of approximately 1 billion people worldwide.

There have been many eminent critics of the Borlaug approach to improving world food production, including the ecologist Vandana Shiva in India, who said that the long-term cost of dependency on Borlaug's new varieties and technology, increased soil erosion and the crop’s vulnerability to pests and reduced soil fertility and genetic diversity.

The rapid spread of semi-dwarf wheat throughout the world was also said to have a negative impact on cereal biodiversity, because the semi- dwarf wheat cultivars took over vast areas of land that had been under small farmer production of a wide variety of “landrace” cultivars. However, developing country breeding programs quickly incorporated their locally adapted germplasm into the semi-dwarf cultivars from CIMMYT. As a consequence biodiversity of their wheat cultivars is generally higher now than it was before the Green Revolution.

Critics have stated that not only did Borlaug's "high-yielding" cultivars demand expensive fertilisers, but they also required more water. In many developing countries both water and fertilizer were, and still are, scarce. The revolution in plant breeding was said to have led to rural impoverishment, increased debt, social inequality and the displacement of vast numbers of peasant farmers.

Borlaug had several robust replies. One of which was the acknowledgement that his Green Revolution had not “transformed the world into Utopia”, but added that many of the critics of this Revolution have “never experienced the physical sensation of hunger. If they lived just one month amid the misery of the developing world, as I have for 50 years, they'd be crying out for tractors and fertiliser and irrigation canals, and be outraged that critics were trying to deny them these things.”

Download pdf